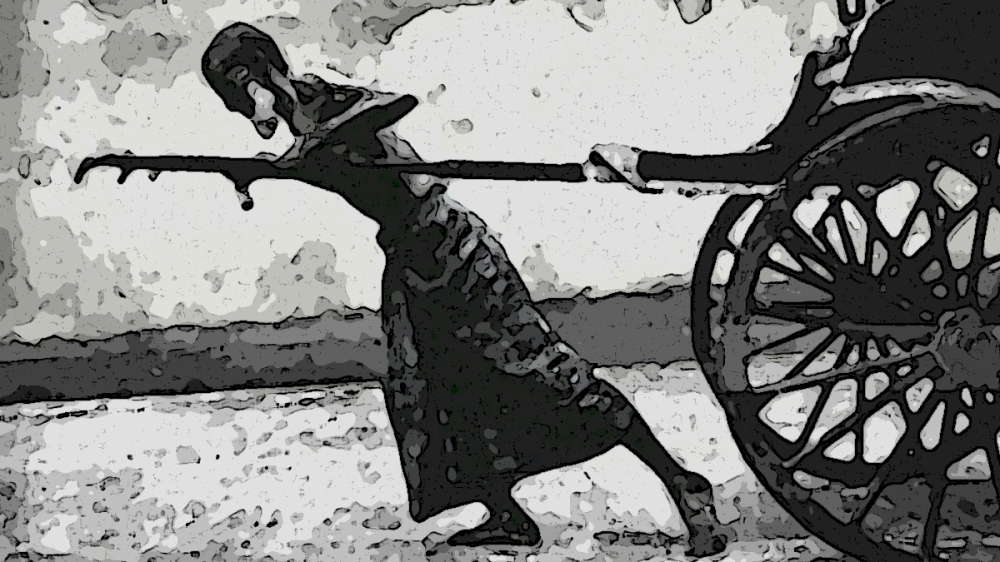

In 1869, in the land of the rising sun, an innovative individual found a brilliant up-gradation for the Kago, a sedan chair form of human transportation carried by two persons. He attached two large wheels to a seating cradle with two extended arms, which allowed a single human being to pull the vehicle. This new rolling cart on wheels was called the Jin-riki-sha, wherein jin meant human, riki meant power, and sha meant conveyance.

It took another five years for this revolutionary personal transport to reach the shores of China from Japan, from where it gradually spread to Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and India. For the millions of poor, illiterate, and unskilled men living in the cities, this cheap means of transportation soon became a minimal source of income.

A hundred-and-fifty years later, in 2019, sixty-year-old Mustafa Miyan earned a meagre living of around two hundred rupees per day, pulling a similar Jin-riki-sha in the streets of the ‘City of Joy,’ Kolkata. A century earlier, in 1919, the British had passed the Hackney Carriage Act allowing the hire of hand-pulled rickshaws in the city as passenger transport vehicles.

Using a man to pull another human served the British well to reinforce their master-slave power hierarchy in the colonies. Though the British were long gone from the country, men like Mustafa continued living a life of servitude, pulling another person for a few coins.

Though post World War II as colonialism declined in Asia and the hand-pulled rickshaw gradually ebbed away from the erstwhile British colonies, strangely, it continued to operate in the streets of Calcutta, becoming a contradictory icon of the vibrant metropolis. It continued to trot in the port city long after India’s independence in 1947. On one hand, it was a relatable image of the city, and on the other, a depiction of shameful reality.

Even the pro-labour-class Communist Government that in China had been successful in banning the hand-pulled rickshaw in 1949 was unable to take it off the streets during the thirty years of their unchallenged rule in the ‘City of Joy.’ In 2019, there were an estimated fourteen thousand unlicensed and five thousand licensed rickshaws in the metropolis. It was savage and despicable to see human horses continue to pull people and load in the heat and rain for a few coins for eighteen hours a day in the twenty-first century.

Every year during the lean agricultural season, Mustafa Miyan would come to the city for four to five months from his tiny and obscure village in Bihar to drive one of these rickshaws. For a hundred rupees per day, he would rent one from a Sardar or a rickshaw owner from a Khatal, a garage and try to earn to survive and save a little to take back to his village at the end of his city stay.

From being the first Indian city to construct the underground metro rail to having electric-powered tramcars on tracks sharing the road with other traffic to operating launch boats across the River Ganges, Calcutta had the most varied mix of transportation compared to any other city in the country.

The culturally rich port city had been the capital of British India since 1772. Much of the development of transportation in the vibrant metropolis was due to the Brits. Since the East India Company was heavily into the opium trade with China, Calcutta already had a decent population of Chinese. Fleeing devastating famines and political upheaval in their land behind the great wall, they arrived in the city during the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century. These immigrants from cities like Canton, Shanghai and Hong Kong were the ones to introduce the hand-pulled rickshaw in the city streets.

In 2019, while most of the next-generation Chinese doing quite well in life had migrated to developed western countries, the hand-pulled rickshaw remained with the poor men of the city. It continued to be a source of meagre income for seasonal migrants such as Mustafa in the boiling metropolis.

Lying on a swinging hammock, tied between a streetlamp and his rickety rickshaw, Mustafa looked up at the smoggy night sky of the city with dimly visible dots of stars scattered here and there. Fixing his gaze on the pale moon playing hide and seek amidst the floating clouds, he wondered how his life had turned.

Back in his village, there was hardly any source of decent income. His wife looked after the household and stayed indoors. It was shameful in his village community for women to venture out of the house to earn. Three of his elder sons lived detached lives with their wives and children in the slums of other cities. Both of his youngest sons, whom he had at a very late age, were still in school. He could not send them to work, at least not before four more years. Next year his only daughter would be turning eighteen, and he had to get her married. The villagers gossiped that it was already too late to get her hitched. He had very little money saved and had to earn much more to get a decent groom by paying a proper dowry.

Since he did not own any land, his only source of income back in the village was to work as a hired farmhand for a few months; the rest of the year, he was pulling a rickshaw in Kolkata, slowly spoiling his health, and earning peanuts. “Why have you forsaken me, my Lord. Though I slog from dawn to dusk, I can never save enough. Show me a sign, guide me, tell me what to do? I am ready to work harder,” shouted Mustafa looking at the stars. “Keep your voice down, you old goat. Unlike you, some of us are trying to sleep here,” mumbled another rickshaw puller sleeping nearby.

In the dim silo rays of the streetlamps and the occasional bouncing beams of cars passing by, one could see a dozen rickshaw pullers lying beside their wooden chariots on a footpath under the porch of an old and neglected North Calcutta villa, which once dazzled with light and life. Like the mansion, they were also the last of their kind, surviving in a nostalgic city that would simply not allow their profession to die.

“Git oppp rickshaw wolaaa… gittt ooop… Tackkk miii hhhom, tuckkk mmmi hommm,” stuttered a nocturnal drunkard, wobbling and kicking Mustafa’s rickshaw. Unable to sleep anyhow, Mustafa thought, why not? “Don’t fall now. Get a hold of yourself. Sit here on the footpath. Give me a minute to prepare my rickshaw. I will take you home, old-timer,” said Mustafa and started untying his hammock and packing his stuff.

After much hassle, the old drunk finally mounted the shaky vehicle. “HHHooorrriii Ghoshhh Streettt…,” uttered the dazed geezer and sunk into the red rexine coir-filled seat of the wooden carriage. After nearly half an hour of confused trotting around the dimly lit streets and bylanes of North Kolkata, the grey boozer finally recognised his house. “Stoppp ssstop… rickshaw wolaaa… this is myyy hhhouseee…,” blabbered the intoxicated man and fell fast asleep on the rickshaw seat.

Trying to wake up the nuisance of a man, Mustafa realised that the drunk was carrying a bag full of cash. Suddenly the honest Musulman was torn between right and wrong. After a spell of internal contradiction that seemed to him like hours of torment, Mustafa reached and took out a fifty rupee note from the bag.

“It’s just a fifty rupee note in such a load of cash. I am sure the boozy would not notice. Forgive me, Lord, it’s not for me but the survival of my family,” thought Mustafa and woke up the old man, who counted and gave him three ten-rupee notes for the ride from the bag. After leaving the man, Mustafa took the fifty rupees note and vowed only to spend it for his daughter’s dowry and neatly hid it in the compartment under the red rexine coir-filled seat of his wooden chariot.

The drunkard started coming every night, and soon the poor rickshaw puller and the rich barfly with a bagful of cash became friends. The boozy owned a liquor shop just around the corner with a hidden and illegal bar counter at the back. He carried a portion of the day’s black money in cash back to his home every night. Chatting during their shaky rides through the dimly lit desolate streets at ghostly hours of the twilight, they came to know much about each other’s life.

While the drunk came to know and sympathise with Mustafa’s frail and helpless family in the village and their poverty-stricken life, the poor rickshaw puller got to know that the rich man had no one in his life. He had lost his wife and two sons in a road accident four years back and punished himself by drinking all the time for being behind the wheels of the car and the only survivor of the crash that dreadful night.

By the end of their ride every time, the old man would fall asleep in the rickshaw, and Mustafa would pull out a note or two from the drunk’s moneybag. Then he would shake and wake up the geezer, who counted with great concentration and gave him thirty rupees every night.

Time passed by, and Mustafa stole from the babu every twilight. Sometimes he pinched as little as a ten-rupee note and at times could not control himself and grabbed a couple of two thousand bucks. Despite making a lot of money, he was not at peace. Thieving was tearing him up from inside. While he had come to consider the lonely man as his friend and hated stealing from him, he could not stop himself from accumulating this God-sent wealth. He sent word back home that he would remain in the city for a few more months and would only return as a wealthy man.

By the end of a year, the little compartment under the red rexine coir seat of Mustafa’s rickshaw overflowed with cash. It was enough to pay for a rich man’s ransom. It was enough to pay a handsome dowry for his daughter, take care of his sons’ education for a few years, open a small shop back at home, and even buy a rickshaw of his own. Amidst all this joy of hope, Mustafa still could not find his peace of mind.

Then one Thursday evening, on the weekly day off at the wine shop, the babu came to the porch of the old and neglected North Calcutta villa where he usually met Mustafa. “Have any of you seen Mustafa,” he enquired with the others. “Today morning I saw him return his rickshaw to the Sardar of our Khatal. He left for his village saying that he would never return to the city to drive a rickshaw again,” said Sujan, one of the other rickshaw wallas. “What an ungrateful fellow. He should have at least said goodbye before going,” angrily uttered the babu and walked away from the old villa.

Later that night, the babu did not touch a drop of hooch. Lying on the sparkling seat of a brand new electric toto rickshaw parked in his garden, he looked up towards the smoggy night sky and angrily wondered, why had he wasted a lakh of rupees buying this vehicle? He had bought the e-rickshaw that morning and had come to call on Mustafa in the evening to give him the surprise.

What the babu did not remember was what had happened the previous night. He had drunk too much and was out cold from the moment he mounted the rickshaw. That night he had even forgotten to fill his bag with cash. On the road, they were stopped by a group of thugs. These men had been observing the old drunk for some time and planned to loot him that night. Not seeing any cash and finding him unconscious and useless, they lost their patience and were about to slit his throat to douse their frustration.

Back in the small and obscure village in Bihar, Mustafa lay in his bamboo cot looking up at the stars. They were much brighter and denser there compared to the smoggy city sky. He smiled, knowing that he had saved his friend’s life. Though he did not have any money, he had peace of mind.

Copyright © 2022 TRISHIKH DASGUPTA

This work of fiction, written by Trishikh Dasgupta is the author’s sole intellectual property. Some characters, incidents, places, and facts may be real while some fictitious. All rights are reserved. No part of this story may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including printing, photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, send an email to the author at trishikh@gmail.com or get in touch with Trishikh on the CONTACT page of this website.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Trishikh Dasgupta

Adventurer, philosopher, writer, painter, photographer, craftsman, innovator, or just a momentary speck in the universe flickering to leave behind a footprint on the sands of time... READ MORE

Amazing and so nice to read this dear friend💞🤗

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much Yaksh.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always a pleasure dear friend! Your works are really so amazing. Just keep going and keep inspiring us with your such posts. Stay happy and stay connected dear friend!🤗💞😊🌹💕

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am so glad that my stories appeal to you. Believe me nothing else gives me more joy. Wishing happiness to you too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always a pleasure dear Sir. And I’m also glad that My comment makes you happy!💕🤗🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

The pleasure is equally mine Yaksh.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You deserve it Dear friend🤗❤😊

LikeLiked by 2 people

Peace of mind through positive action can be sought regardless of one’s class or monetary status.Is that a path to achieve “Karma” to a better future life?

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are absolutely right – Peace of mind is always attainable. It can certainly be a means to achieve Karma, as with peace comes the gift of focus and thought, precursors to any action, which may lead to points for Karma.

LikeLike

Let both of us then share that peaceful means to obtain Karma. Take care.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are absolutely right my friend.

LikeLike

We spread hope of karma through our stories I hope

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is also very true.

LikeLike

I would like to know more about karma at this point in my life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think Karma is just “Return On Investment.” The way we invest our time, nature, and being in relations to other beings and things, will give us certain returns, if not immediately, certainly in the long run, that is Karma according to me. Many religions believe, that many a time the action and its return cannot be completed in a single lifetime, so the concept of rebirth, till our Karma becomes perfect and one can attain moksha or escape the life and birth cycle.

LikeLike

I’m hopeful about every thing you said except the word perfect?

How many lifetimes would it take to be perfect?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, perfection is something that we should perhaps never attain even if through some miracle we can. For once we reach it, we will not have a purpose anymore.

LikeLike

So here’s to imperfect. I’m game!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too friend, me too…

LikeLike

BUON W.E.

SALUTI

LikeLiked by 2 people

A great weekend and a prosperous week ahead to you too.

LikeLike

GRAZIE MILLE GENTILISSIMO, CONTRACCAMBIATA.

LikeLiked by 1 person