The Lower Circular Road Cemetery woke each morning before the city of Kolkata did. Before trams clanged awake, before kettles whistled in nearby kitchens, before the first newspaper slapped against a veranda floor, the cemetery breathed, slow, ancient, and vegetal. Dew clung to marble like unshed tears. Moss thickened the edges of bevelled names on cold stones that once commanded rooms. Leaves fell with the patience of monks. And beneath the greatest banyan, in this grove of the dead, its roots dropping from the sky like the braids of time itself, lived the old man Botuk on a wobbly bamboo charpoy.

The greybeard never slept or spent much time in his allotted single room quarter, which he only used for storing some of his belongings. He mostly lived under the banyan, and had been here so long that even the cemetery guards who came and went spoke of him like a fixture: the old caretaker, the man who knows every grave, the one who talks to the dead as if they might answer. Botuk did not mind. The dead, at least, did not hurry away when he spoke or smiled.

The old caretaker’s day began with sweeping, slow arcs of the broom tracing the curves of paths laid out in the 1840s, when the city christened by the British as Calcutta was still learning to pronounce itself as the Empire’s prized “Jewel in the crown.” Botuk’s broom raised the smell of wet leaves, bat droppings, old flowers, and stone dust. It was a smell that he loved. And it smelled like the truth.

As he swept, he greeted the graves softly, the way one greets elders. “Good morning, Dotto-babu,” he murmured near the resting place of Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the poet who had loved too fiercely and died too young, who had ventured far from home to earn a name in English Literature, only to return to Calcutta and find literary pleasures in his mother tongue, Bengali. Now resting eternally, buried in the soil of his beloved city with his wife Henrietta beside him. Jasmine often crept here, white and stubborn. “Bethune-saheb,” Botuk nodded at the tall, restrained monument of John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune, whose belief in educating women had once caused polite outrage and later a quiet revolution. He paused longer near Charles Freer Andrews, Deenabandhu, Mahatma Gandhi’s friend, whose stone seemed less cold than the others, as if compassion still radiated faintly from it. Botuk knew their stories, not from books, but from years of listening to historians, wanderers, grieving families, and sometimes from the stones themselves. For stones speak, if you are willing to listen, and give them time. And time was something that the old man had.

Though once, long ago, he had a different life. He had been a tram conductor in north Calcutta, ringing bells and shouting stops, his voice strong and certain. His wife Kamala sold flowers near Sealdah, marigolds in the morning, tuberoses at dusk. Their Christian home was small and always smelled of rice, incense, and wet earth. On winter nights, they slept close, sharing warmth and dreams. Their son Ratan was born during Durga Puja, red-faced and loud, as if announcing himself to the world.

Then, time did what it always does, bringing change, sometimes rise and sometimes downfall. For Botuk, it was the latter. The man lost his job, and their financial condition deteriorated very fast. Kamala fell ill one winter that felt colder than others. Fever lingered. Medicine drained their savings. The house grew quieter. One morning, Botuk woke to a silence so complete it felt like being buried alive. Kamala’s face was peaceful, almost smiling, as if she had slipped away mid-thought.

Botuk could not buy a burial spot for his wife at any cemetery. Since he was a non-practising Christian not associated with any church, his wife could not even get a pauper’s burial. Instead, the boys of a local club paid for her to be cremated at the Nimtala ghat, from where he brought her ashes in a little earthen pot. He kept it on a shelf at home with trembling hands and a heart hollowed out like a gourd. After that, the house changed. Ratan grew restless, angry at the world for stealing his mother. By the time he was twenty, the city felt too small, his father too broken. One afternoon, after a sharp argument that ended in words neither could take back, Ratan left with a backpack and a promise to write. He never did. Botuk waited years. Letters became prayers. Prayers thinned into habit. Habit turned into silence. It was around then that he got the job at the cemetery. At first, it was only work, and later, it became a refuge. Eventually, it became home. And many years passed.

By the week before Christmas of 2025, the cemetery changed its mood. The air sharpened. Mornings carried a faint smell of wood smoke from nearby shanties. Somewhere beyond the great walls, churches rehearsed their choirs, broken fragments of hymns floating in like wandering souls. Bells practised patience.

Sometimes, after his morning rounds, Botuk stood near the main gate and listened to the world outside. At the junction of Mother Teresa Sarani and Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Road, life roared. White cabs honked and zoomed by, rickshaws creaked under impossible loads, and buses exhaled tiredly. The air carried layers of smell, hot oil from telebhaja or fritter stalls, sweet jhalmuri or spicy puffed rice mixed with coriander and lime, Mughlai dishes such as Nihari and Biryani brewing overnight to serve early bird meat-loving breakfast seekers, diesel fumes sharp as reprimands. From nearby mosques came the call to prayer, rising and falling like breath itself, echoing through lanes where Muslim families lived cheek by jowl with mechanics and traders. Across the road, the aftermarket car-parts bazaar gleamed with metal, spark plugs, tyres, and steering wheels stacked like offerings. Oil, rubber, rust, and sunlight mingled there. Schoolchildren in neat uniforms cut through the chaos, laughter bouncing off walls, shoes scuffing purposefully toward buildings hidden behind peeling facades.

And if Botuk turned his head just so, he could feel the pull of Park Street, the slow brightening of windows, Christmas lights strung across the wide road, wreaths climbing glass, bakeries perfuming the air with butter and sugar, jazz notes rehearsing themselves for nightfall. Life rushed past the cemetery walls, noisy and insistent. Inside, time rested its bones.

On the morning of Christmas Eve, Botuk was repairing the hinge of the back gate, the one that never appeared on maps, when he heard hurried footsteps. The street children came together, quieter than usual. Pintu led them, his face streaked with grime and something wetter. In his arms lay a small black puppy, its body unnaturally still, one ear bent like a folded leaf. “It happened on the road,” Pintu said. “The car didn’t stop.”

The puppy had followed them for weeks. Slept in their pile of rags. Licked their fingers clean of cheap biscuit crumbs. Barked bravely at shadows much larger than itself. Botuk knelt slowly. He touched the puppy’s fur. It was already cooling. “I’m sorry, little one,” he whispered. They asked no questions. They already knew the answer. They wanted to bury him somewhere where the little soul could be remembered.

They moved through the cemetery together, Botuk leading, children following, the city held at bay by high brick walls and ancient trees. The banyan watched them approach, its aerial roots swaying slightly, as if acknowledging old acquaintances. They searched for soft ground, away from marked graves. Botuk knew every patch where earth still remembered how to yield. As he pressed his fingers into the soil near a tangle of roots and fallen flowers, his knuckles struck stone.

A tiny headstone emerged, barely visible beneath moss and time. Botuk brushed it clean. The inscription was faint but legible, the words carved with care: “Roscoe, faithful friend. In fields of light may you run again. 1894–1899.” Nothing more. The children stared. Pintu traced the letters with his finger, reverent. “Another dog?” he asked. “Yes,” Botuk said, his voice thick. “Long ago.”

A man had been watching from a distance, a tall figure with a notebook and a scarf looped twice around his neck. He approached now, careful not to disturb the moment. “I’ve been looking for something like that,” the man said softly. “I’m a historian. Pet burials here were spoken of… but never recorded properly.”

Botuk looked at him, surprised but not displeased. “They were loved,” Botuk said simply. “That was enough.” Together, they buried the puppy beside Roscoe, earth closing gently, as if tucking a child into sleep. The historian listened as Botuk spoke, not just of Roscoe, but of other stories: a pony buried near a fence after carrying a child for years; a parrot whose owner carved verses for him; dogs who crossed oceans and never left their masters’ sides. “Official records forget,” Botuk said. “But the ground remembers.”

After burying the puppy, the children left. The historian wandered off between graves, making notes in his book, and Botuk went to tend to unwanted vegetation on ancient and recent graves. And that night, as always, Botuk opened the back gate. The children slipped in like shadows, gathering near the small fire he built with practised hands. Flames crackled. Smoke rose straight into the cold sky. The historian appeared, notebook closed, listening instead, it seems he had not left the place.

Botuk told stories. The historian added dates, contexts, and voices from old letters. Together, they painted a world where love crossed species and centuries. The children listened wide-eyed, warmth creeping into their fingers and hearts. Above them, the banyan whispered. Leaves rustled. Somewhere far away, a bell rang once. And then another.

Christmas morning arrived gently. Light filtered through fog like forgiveness. The cemetery glowed, stones pale gold, dew sparkling, birds daring the cold. Church bells rang fuller now, confident, joyous. Botuk walked the paths more slowly than usual. He felt something unfamiliar in his chest, not an ache, but a lift. Near the banyan, someone had placed flowers. Fresh. Red and white. Botuk knelt – for Kamala, for Ratan, wherever he was, for Roscoe, for the puppy, and for himself. From beyond the wall came laughter, children running, a hymn rising, life insisting. Botuk stood beneath the banyan’s vast shadow, no longer lonely, just rooted. Christmas had come, not to erase loss, but to soften it. Love had found him again. And the cemetery breathed on.

Copyright © 2025 TRISHIKH DASGUPTA

This work of fiction, written by Trishikh Dasgupta is the author’s sole intellectual property. Some characters, incidents, places, and facts may be real while some fictitious. All rights are reserved. No part of this story may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including printing, photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, send an email to the author at trishikh@gmail.com or get in touch with Trishikh on the CONTACT page of this website.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Trishikh Dasgupta

Adventurer, philosopher, writer, painter, photographer, craftsman, innovator, or just a momentary speck in the universe flickering to leave behind a footprint on the sands of time... READ MORE

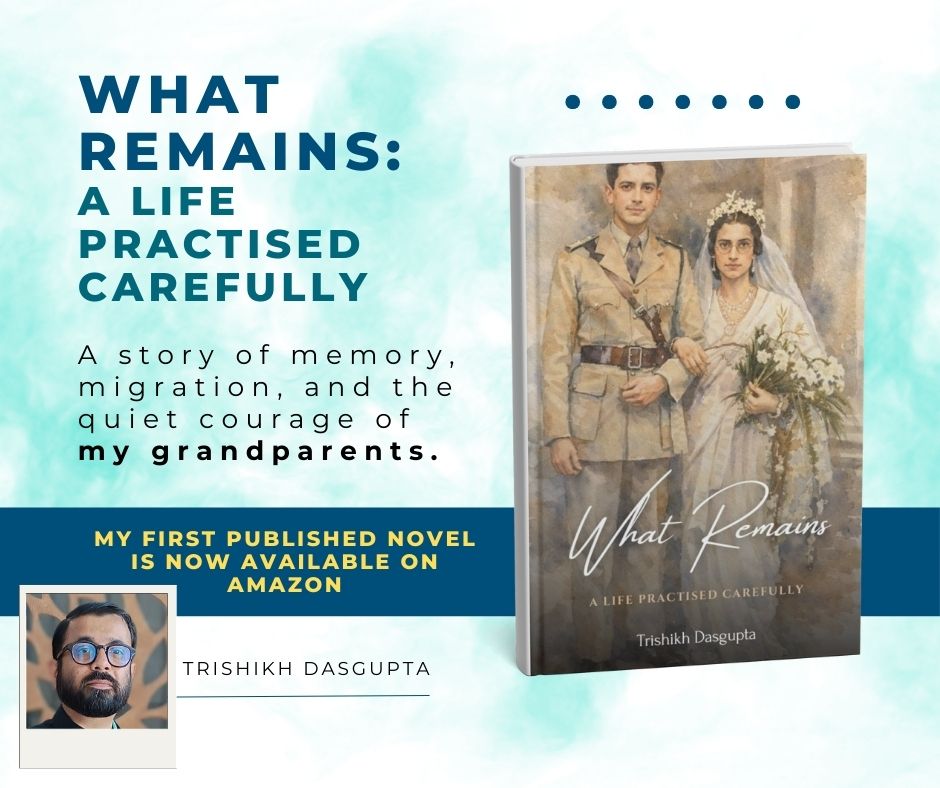

These stories are Free and if you have found something here that stayed with you, some of my other books are now available in print and digital editions. They gather longer journeys, quieter questions, and stories that continue beyond this page.

This is a profoundly moving and exquisitely crafted piece—quiet, humane, and deeply rooted in place and memory. From the opening breath of the Lower Circular Road Cemetery to the final, forgiving light of Christmas morning, the prose carries a rare patience, as if it knows that the most important truths cannot be rushed.

The sensory detail is extraordinary: the smells of wet leaves and stone dust, the pulse of Kolkata beyond the walls, the way history, faith, commerce, and everyday life coexist in overlapping rhythms. The cemetery becomes more than a setting—it is a living archive, a witness, a sanctuary where time does not stop but learns how to rest. Botuk himself is beautifully drawn: gentle, broken, resilient, and deeply human. His tenderness toward the dead, the children, and the animals feels earned, never sentimental, and quietly devastating.. Truly memorable work.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thank you, Verma’ji, for reading the story with such patience and care. Your words feel like you walked the cemetery paths alongside Botuk, listening when the stones spoke and when they chose to stay silent.

I’m deeply grateful that the rhythms, the smells, the pauses, and the small mercies found their way to you. Botuk, the children, the animals, and that resting ground were all trying to say one simple thing—that love lingers, even where time slows down.

Your reading has given the story another life. For that, I’m truly thankful.

LikeLiked by 3 people

🙏

Aum Shanti

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you so much.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I will read this soon. Either it is going to be very very sad or very very happy. A mix of both possibly. But as always I know it will be profoundly beautiful.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Do read when you get the time. I leave the suspense of the mood of the story for you to find out when you read it. I am sure that you would like it, like the rest of my stories.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I love your stories. They should be compiled into a book and made readily available in stores and online. That way they can truly become immortal.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That has been a very long dream of mine. This was my 96th Short Story, soon it would be 100 – after that I plan to aggressively look for a good publisher who will treasure my kind of writing, and publish a collection of my short stories.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Your stories are a treasure

LikeLiked by 3 people

I just read this story before bed! Beautiful and wonderful! I have long wanted to befriend a soul like that. Someone lonely who just needs a friend. I remember loneliness very well. And sometimes I still feel it. And I swore if I could help someone I would.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That is such a noble thought. I too always look forward to opportunities to help others, but to be friends with someone who lives a solitary existence, is very noble indeed.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think your character is very wise. It would be interesting to have series of quiet adventures with him and the man who is a historian. Followed by the children. Perhaps as they learn forgotten histories and personal stories of local Indian families.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is a very creative suggestion. Who knows perhaps I would do some more stories, and make it a series.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would imagine the historian eventually moving in with your other character. And becoming life long friends.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That would be a really nice way to write about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well it’s just an idea at any rate. The truth is, one could make a series about all of your stories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that is actually true. I have thought many times to write a sequel on some of my stories, but have not been able to decide on writing. Every time I sit to write, a new story flows out on the paper for now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s amazing. Allow yourself to follow your gut. It will come to you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice story and loved the descriptions as always.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thank you Savitha, so glad that you liked the tale. Always a pleasure to share a story with you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What can I say, dear Trishikh, only that you have a great gift to make your reader live in your stories, experience the events described as if one was present, and sometime feel the tears of emotions that your tales bring on. As your devoted reader, I have to thank you from the bottom of my heart for taking me every week on the unforgettable journey.

Joanna

LikeLiked by 5 people

Dear Joanna, I am so thankful to God for having found a dedicated admirer of my stories such as you. Your constant appreciation gives me a lot of encouragement to keep on writing these stories.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you, Trishikh, for the beautiful reply! As always, you are more than welcome!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 3 people

What a lovely tale.. I enjoyed it very much.. thank you ❤️

LikeLiked by 5 people

Dear Fiona, thank you so much for always appreciating my stories. So glad that you liked my latest tale too.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Auguri di Sereno Buon Natale, Trishikn!👋😊🎄☃️

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thank you so much.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My eyes welled up with tears as I weaved through the story and came to its end. Thank you for bringing Botuk to us.

LikeLiked by 4 people

You are most welcome Kajoli. I am so happy that my story spoke to your emotions.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you Ned for sharing my 96th short story on your website.

As we step out of Christmas, when the bells fade and silence speaks, I am happy to have been able to share this beautiful story – A cemetery, a banyan tree, an old man who listens to stones, and a small puppy who teaches us that even the unloved are remembered, and that love is never truly buried.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another good story. I meant to tell you that your writing often reminds me of Durrell and his Alexandria Quartet. Good work.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you so much Ned. That is such a massive compliment.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Lovely writing, human, touching, atmospheric, and full of echoes.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you so much Michael. So happy that the story touched you in such a unique way.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Beautiful story, very moving. Thanks for sharing. – Dave

LikeLiked by 3 people

You are most welcome Dave. I am so glad that the story felt so moving to you.

LikeLiked by 3 people

This is so touching, The tiny details of an ordinary morning makes it so extra-ordinary. A small happening can make a person’s day.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That is so true, a small occurrence can really make our day.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, they do. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a deeply moving story, rich with emotion, and its timing makes it even more poignant. Thank you, Trishikh, for yet another beautiful tale.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Dear KK, I am so happy that you liked this story of mine so much. I treasure all your appreciation over the years. They continue to give me a lot of encouragement.

LikeLiked by 3 people

You’re welcome, Trishikh!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awe how sad was this? what a great story and so believable.. merry christmas..

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, I did not want to make this sad, however as I was writing the story, I felt compelled to write the realities of life, and the story turned out to be on the sadder side. But I feel that it has a positive message also.

Thank you for your beautiful comment. Our conversations give me great joy.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this lovely story. I enjoyed the power of remembrance that Botuk gifted to the children and the world. As always you wove history and humanity together in an honoring way.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Dear Katelon, you are most welcome. I am so happy to have been able to write and share this story. Thank you so much for your beautiful words.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a poignant, heart melting post.

You have surpassed yourself in narrating a transcendental love story.

I am at a loss for words.

So moving.

The description brought to life every nook and cranny of that old cemetery and the city of joy where sorrow too resides quietly almost surreptitiously.

The ups and downs of human life are intricately woven into the saga of mankind – history of evolution and birth, decay and destruction of human civilization.

You have written this story with a lot of heart.

LikeLiked by 3 people

So glad that you think about the story with such deep emotional affection. I wanted to write a happy story during Christmas, but as I kept on thinking about it, and started to write it, mixed emotions about happiness and realities of life kept creeping into my mind, and the byproduct was this story.

I won’t say that this is a sad story though, it is very realistic and perhaps how life is. Sadness and joy, being an integral part of experiencing life. And if we want we could perhaps find any of the two in any situation of our lives. We humans have the ability to change our thoughts and direct them towards any state of mind we may want.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The story produced a kind of mixed feelings like sadness but there was a strange beauty in it. There is a particular word for it but I am unable to remember it now.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The word you are looking for is perhaps ‘poignant’ or ‘bittersweet’. Am glad that you liked the story.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Trishikh,

This is an absolutely beautiful story, drenched in gorgeous writing that makes the story come so alive we are there. “Dew clung to marble like unshed tears…” that whole paragraph was so wonderfully poetic… it was astounding. 😍🙏🏽

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. Words that read like a Movie are my favourite. I always try to attain this in my stories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bittersweet is correct. But there is another untranslatable word too – perhaps Japanese or in some other language.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Japanese ‘mono no aware’ captures the gentle sadness at the transience of things, and Japanese ‘wabi-sabi’ finds beauty in imperfection, creating a sense of poignant beauty.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You captured this story well. Christmas is not always filled with happiness for many. Have a good Monday.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That is so true. Christmas like any other time of the year can be a time for both sadness or joy for someone. I think the message of peace, joy, love, and forgiveness is something that we especially remember during this time.

A great Monday and an awesome week ahead to you too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another breathtaking piece by you…

the cemetery isn’t a place of ending, but a place of continuity. Botuk represents the best of us: the ability to take a heart hollowed out like a gourd and fill it back up with the stories of others. By burying the children’s puppy next to a dog from 1894, he bridged a gap of 131 years with a single act of empathy. It reminds me that while we cannot stop time doing what it always does ….we can choose to be the ones who listen when the stones speak. 🗣️

May your new year be like that morning light—filtering through the fog like forgiveness. I hope the coming months bring you the same lift in your chest that Botuk felt—a sense of being deeply rooted and no longer lonely. May you find beauty in the quiet corners, stories in the stillness, and may your own faithful friends always find a place of warmth by your fire.

Thank you for sharing this beautiful, haunting, and ultimately hopeful journey.😇🥰

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Aparna, for reading the story with such tenderness and generosity. Your words feel like an extension of the banyan’s own listening, attentive, unhurried, and kind.

What you noticed about continuity and bridging time is exactly where Botuk lives, in that quiet space where loss does not end love, it only changes its language. The act of laying one small life beside another, separated by a century and more, felt to me like a refusal to let affection be measured by time.

Your best wishes for the year ahead means more than I can say. If the story carries even a fraction of that morning light you speak of, then it has done its work. Thank you for sitting by the fire, for listening when the stones spoke, and for reminding me why these quiet corners are worth returning to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy New Year, Trishikh!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Joanna,

A very Happy New Year to you and your loved ones too. May 2026 bring new hues of positive life and breathtaking experiences.

Trishikh

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Trishikh, and likewise!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 1 person

What stays with me is the sense of presence—how Roscoe is allowed to simply be, without explanation—and how the others are held with the same quiet respect. The stillness in your telling feels deliberate, as if attention itself is the act. This remains with me, in the way moments do when they are truly seen.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Livora, your words of appreciation come as a gift on the eve of a new year. Your comments have always given me great encouragement. I can never thank you fully for being such an ardent fan.

Wishing you and your loved one a wonderful 2026 ahead.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Trishikh, thank you for such gracious words. Knowing that my presence and responses have encouraged you over time is something I hold quietly and gratefully. Your writing has always offered me moments of stillness and clarity in return. Wishing you and your loved ones a year ahead filled with calm strength, gentle light, and stories that continue to speak with depth and grace.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Livora, I shall do my best in writing many more of such stories.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Happy New Year 😊 ✨️ Trishikh

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy New Year to you and your family too.

LikeLike

Beautiful story as always. Wishing you a very happy new year 🥳

LikeLiked by 2 people

A very Happy New Year to you and your family too Priti. Have a great 2026.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

We couldn’t agree more with MiamiMagus, who so beautifully wrote: “I love your stories. They should be compiled into a book and made readily available in stores and online. That way they can truly become immortal.”

Wishing you and your family a very Happy New Year, dear Trishikh, and a bright, successful 2026 ahead! ⭐

Sending our very best wishes and positive energy your way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. I have always treasured your support and appreciation for my stories. Yes, it would indeed be nice to get my stories published. A very happy and prosperous New Year to you and your family too.

LikeLike

Check out my site

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, it’s my pleasure to visit your site.

LikeLike

This is extraordinarily beautiful. 👏🙏🏻

The cemetery feels less like a setting and more like a living, breathing witness. One that remembers what people, records, and even cities forget. Your prose carries a rare stillness, the kind that slows the reader down and asks them to listen, not just read. Botuk is tenderly drawn, and through him you honour grief without sentimentality, love without announcement, and time without haste.

This is storytelling at its most humane: rooted, reverent, and deeply kind. A piece that lingers long after the last sentence, like the echo of a bell on a cold Christmas morning.🙏🏻💛

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for this generous and deeply felt reading. I am moved by how attentively you listened to the stillness of the story, because that quiet was as important to me as any sentence written.

I am grateful that the cemetery revealed itself to you not merely as a place, but as a witness, holding what people and records often let slip away. Botuk exists in that space of listening, where grief is allowed its dignity and love does not need to declare itself loudly to be real.

If the story stayed with you like a bell echoing on a cold Christmas morning, then it has found its purpose. Thank you for carrying it forward with such kindness and care.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Trishikh. The care with which you listen to your own story is what gives it such depth and grace. I’m glad to have been one of the quiet witnesses it found along the way.🙏🏻💛

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are most welcome.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙏🏻💛

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love how you described the cemetery as breathing – it gives it a sense of life, even in a place of rest 🌿

LikeLike

BUON WEEK-END

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. A great week to you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙋♀️ UN SALUTO

LikeLiked by 1 person

Greetings to you and your family too.

LikeLike