When dawn flared on the Persian horizon, it splashed salmon and gold across restless waters, and there, between fierce waves and trembling light, stood Thomas Cananeus, his fingers wrapped around the battered wheel of his ship, his heart still clinging to the echo of burning homes and frightened faces. It was the fourth century, sometime between 345 and 811 AD, but the air on the docks of his homeland was as fraught as any battlefield. Once thriving markets now whispered of persecution. Reed-lanterns snuffed out in narrow alleys, and children huddled beside mothers who trembled more with fear than with cold. Somewhere beyond the date palms and caravans of Mesopotamia, a wind spoke of a distant coast where temples didn’t hunt believers. Ever since that murmur reached his ears, a promise carried by some trader returning from the mystic south-east, Thomas knew where they would go.

They – the forgotten ones. Seventy-two families, nearly four hundred souls of Syriac-speaking women, men and children who had traced the line of Jesus’ earliest Followers in their prayers, who bore the songs and symbols of the Christian faith in their tongues and hearts. They were weavers and shoemakers, bakers and fishers; but above all, refugees of the spirit and the flesh. The talons of the Sassanian Emperor’s cruelties had clasped around their throats with such force that even daylight seemed a threat.

Thomas could see it in their eyes, the moment they gathered at the old olive grove before departure. The last trace of a past life, folded and held close, a candle snuffed before the flame could reach its wick. For months, Thomas had bargained with captains and scribes, river folk and desert merchants, pooling every silver coin he possessed. They had borrowed jars of oil and salted figs, flasks of fresh water and woollen shawls for the colder seas. He had arranged ships, promised protection and land, though all of that was a hope born of desperation. Hope, after all, was the only currency left to those on the brink of total annihilation.

When the fleet of three creaking ships finally pushed off from the muddy banks, the hush was sacred, a lull between the pain of leaving known shores and the terror of arriving at an unknown land. For many days, the sea lay restless beneath them. While the dawn smelled of brine and morning sickness, dusks sang with wind and stars so violent in their brightness they seemed to hoard the sky. And all the while, in every cramped corner of the vessel, women hummed old psalms, children clutched amulets of wood and ivory, and men whispered, “Home, we will find again.”

Often Thomas stood at the bowsprit as the first rays of the sun appeared, feeling the salt kiss his eyes, and thought he could hear not just the sea, but the past itself, murmuring: Remember who you are, so those who follow may know the sound of their names. Finally, on one pale and trembling dawn, the lookouts called out “land… land… land.”

A dense green spine cradled by a foaming coastline. It was Kodungallur, the ancient harbour of Muziris on the Malabar Coast of present-day Kerala in the subcontinent of India. Here, the rains spoke in monsoon thunder, and the smell of spice trees wove into every breath of air. And when the ships entered the estuary, it was as though the land exhaled, lush and expectant.

Beyond the heaving prow, the sea softened its voice, turning from a roar into a reverent murmur, as if it knew it was nearing an old and listening shore. The water shifted from iron blue to a tender green, translucent enough to reveal darting silver fish that scattered like spilt light. The air grew heavy and perfumed, salt giving way to wet earth, crushed pepper vines, fermenting coconut husk, and the faint sweetness of flowering mango and jackfruit trees hidden inland. From the mangrove-lined banks rose the low, rhythmic chorus of cicadas, punctuated by the splash of oars and the distant cry of waterfowl lifting from the estuary in slow, startled arcs. Brahminy kites circled overhead, their rust-red wings catching the sun, while white egrets stood like patient prayers along the mudflats. The land itself seemed to breathe – coconut trees swaying, forests whispering, river and sea meeting in a long, sighing embrace, welcoming the tired sails not as intruders, but as remembered guests returning after a very long exile.

Walking the last plank, Thomas felt the earth pulse under his feet. Behind him, the frightened faces of his people peeked from the shadows of the vessels. Before them, the broad sweep of Kodungallur’s harbour – a tapestry of tall palm silhouettes and shining temples that rose like prayers from the green.

Uncertain feet touched sand soaked with salt and hope, the grains warm and yielding beneath weary soles that had forgotten the feel of land. The harbour of Muziris throbbed with life – a living, breathing artery of the world, where the air hung thick with the mingled perfumes of cardamom pods split open, black pepper drying in the sun, fish laid out on coir mats, damp river mud, jasmine garlands, and the faint, resinous smoke of incense drifting from nearby shrines. The quays rang with sound: wooden hulls knocking gently against each other, ropes creaking under weight, oars slapping water, bells tied to pack animals chiming softly as they moved, and voices rising and falling in a dozen tongues – Arabic, Greek, Syriac, Tamil, Prakrit – bargaining, laughing, swearing, and blessing.

The market stalls sprawled along the waterfront in restless colours: mounds of spices glowing like crushed suns, bolts of cotton and silk breathing in the breeze, bronze vessels flashing briefly before being swallowed by passing shadows. Merchants from Arabia and Rome stood shoulder to shoulder with traders from Persia and distant China, their skins and garments telling long stories of deserts crossed and seas endured. Above it all, seabirds wheeled and cried, snatching scraps, while crows strutted boldly between baskets as if they owned the earth. In that crowded, salt-stained chaos, Thomas felt the strange tightening in his chest – the ache of a man who had lost everything, and the quiet astonishment of one who had, impossibly, arrived somewhere he was meant to be.

Word spread quickly that a Syrian merchant of note had landed with his people. Traders and sailors whispered; Brahmin priests cocked their heads with curiosity; the Portuguese hadn’t yet arrived to fill the air with Latin zeal. Into this mosaic walked Cheraman Perumal, the local king, regal yet gentle, eyes warmed by the golden sun. He wore sandalwood paste and silk, and when Thomas was brought before him, the king’s gaze was deep and welcoming, calm as monsoon rain on parched earth.

Thomas knelt, his voice trembling with reverence. He told of persecution, of nights invaded by soldiers, of babies wailing so long that their mothers feared they’d never whisper lullabies again. He spoke of hope, fragile but enduring, and of a yearning for a place where children might pick jackfruit under safe skies, where women might worship the faith of their fathers without fear, and men might toil without dread.

The king heard him. Truly heard him. And in the soft cadence of that moment, Thomas felt something begin to heal, not fully, but in small increments: like sunlight through storm clouds. Cheraman Perumal rose then, and with a voice that bore the rhythm of old rivers, he welcomed Thomas and his people to Kodungallur. Not as wanderers. Not as supplicants. But as human beings, worthy of land, shelter, and the dignity of a future yet unwritten.

That very afternoon, under the shade of flowering mango trees, the king decreed privileges for Thomas and the families: plots of land by the southern bank of the Periyar, permissions to build homes, to cultivate gardens, to trade and to practice their faith without fear. The memory of that grant, etched in copper plates, would age beyond its mortal witnesses and enter legend.

While many whisper that Thomas was a saint, others believe that he was a prophet. And some say that he was just a Syrian Merchant, a humanitarian who, by rescuing persecuted Christians from Syria, planted the seed of Christianity in India. In years to come, the Syrian Christians of Kerala would weave his name into their tale of origins so deeply that for many, he became inseparable from St. Thomas the Apostle of Jesus Christ. Some traditions hold that St. Thomas brought Christianity to India, landing on Kerala soil centuries before Thomas Cananeus in 52 AD, planting church after church across the coast; others say his mission wandered east before fading into martyrdom near Mylapore in the Tamil lands.

Yet history, as Thomas Cananeus knew it, was not a single thread. It was like a knitted heirloom quilt – knotty, woven with many hands, damaged by time, corrected by memory, blurred between what was and what was believed. Thomas of Cana’s story interlaced with these legends, merging into the life of the land – confusing to outsiders, sacred to believers – a rhapsody of devotion and memory where fact and faith incubated like twins in the womb of a land of a thousand religions.

In the weeks that followed, Kodungallur became a cradle of new rhythms. Women sang hymns beneath banana groves. Children played with feathered kites, their laughter rippling like seashell song. Men traded in pepper and cotton, and Thomas watched the sunrise over his people’s small homes, the scent of cooking lentils and fresh fish weaving into the promise of morning.

He stood one evening by the water’s edge, the tide whispering secrets against the shore. A soft wind carried the scent of cloves, and a chill of satisfaction rose within him. He felt the pulse of this place – its welcoming arms, its fertile soil, its vast skies. A destiny born not of violence but of mercy. A future sealed not by war but by shelter. Under a sky stitched with stars, Thomas lifted a prayer, not for the wars behind them, but for the peace ahead – a peace as unfurling and expansive as the sea that had brought them here. In that prayer, the breeze carried the echo of every song sung by those who once feared for their lives – now reborn into this strange and sweet land. And in their children’s laughter lay the promise of a tomorrow that neither storm nor fire could ever take away.

And so, more than sixteen centuries later, that prayer still drifts across the subcontinent like an unfinished hymn. Today, India is home to nearly 30 million Christians, roughly 2.3% of its vast population – Roman Catholics, Syrian Orthodox, Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara churches, Protestants, Pentecostals, and countless small congregations whose faith survives not in cathedrals alone but in kitchens, courtyards, and quiet village chapels. From the ancient churches of Kerala to the hill communities of the Northeast, from coastal Tamil Nadu to tribal belts of central India, they remain a minority – often invisible, sometimes misunderstood, and in recent years increasingly vulnerable to social hostility, church burnings, forced conversions, and legal harassment.

Yet, despite their small numbers, Christians have shaped the moral and civic spine of the nation in disproportionate measure – building some of India’s finest schools, colleges, hospitals, leprosy homes, and centres of care, tending to bodies and minds across caste, creed, and class, often in places the state reached last or not at all. Their contribution is stitched quietly into everyday Indian life – in classrooms where curiosity was first awakened, in hospital corridors where pain met compassion, in remote villages where dignity arrived before development.

And yet, like all human institutions, the Churches in India have not been without shadow – marked at times by corruption, abuse of power, and moral failure, reminders that faith, when worn by fallible hands, can fracture as easily as it can heal. Still, they endure, as Thomas’ people once did – singing softly when the world grows loud, holding their crosses close when the air turns sharp, choosing mercy over anger and memory over fear. Their story, like his, is not one of conquest but of arrival; not of numbers but of persistence, a faith carried not by the sword, but by tired feet, open hands, and the stubborn hope that even in uncertain lands, dignity can still find a home – from Cana to the Coconut Coast.

This work of fiction, written by Trishikh Dasgupta, is inspired by one of the historical narratives surrounding the coming of Christianity to India and remains the author’s sole intellectual property. Some characters, incidents, places, and facts may be real while some fictitious. All rights are reserved. No part of this story may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including printing, photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, send an email to the author at trishikh@gmail.com or get in touch with Trishikh on the CONTACT page of this website.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Trishikh Dasgupta

Adventurer, philosopher, writer, painter, photographer, craftsman, innovator, or just a momentary speck in the universe flickering to leave behind a footprint on the sands of time... READ MORE

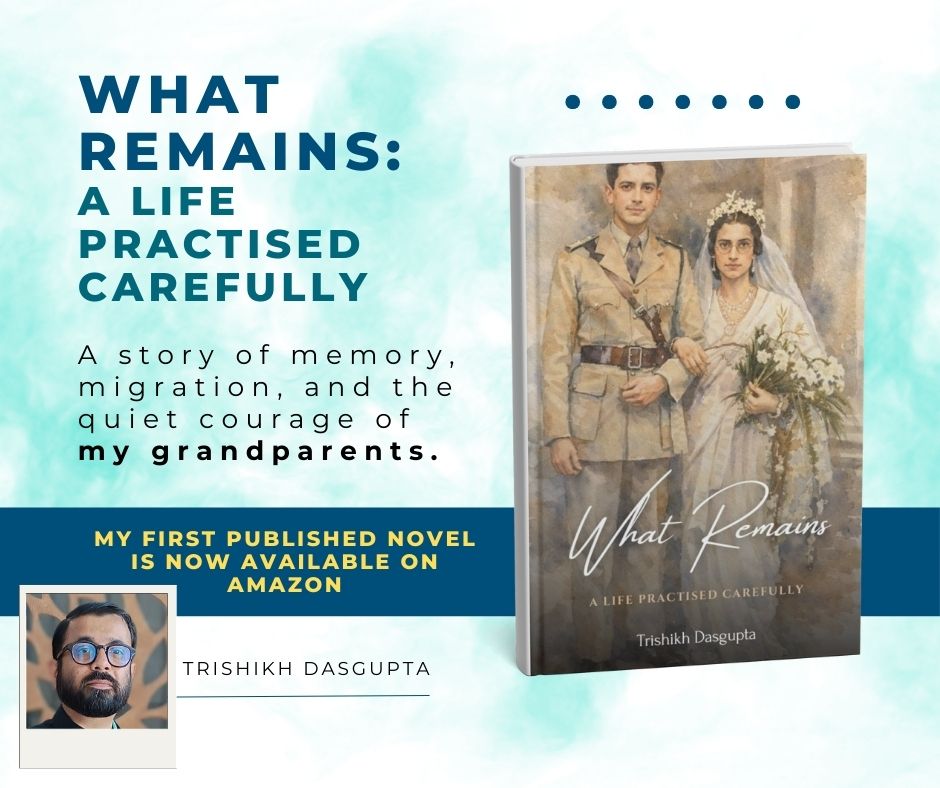

These stories are Free and if you have found something here that stayed with you, some of my other books are now available in print and digital editions. They gather longer journeys, quieter questions, and stories that continue beyond this page.

It is said that Doubting Thomas went to India and they still worship in his church. From there he went to China. About fifteen years ago the people in a village in China proved they came with Thomas From there he went to Hong Kong and built a church that still stands. His final destination was southern Japan where he converted a local princess to Christianity. It is said that a few still know his burial place

I was shocked to learn of this while teaching in China and having Japenese Christian friends

LikeLiked by 5 people

Yes, I too have heard about this version of the History, about the Apostle Thomas visiting India and then moving on to China. But did not know that he went to Southern Japan, and died there. There are so many claims of his final resting place. There are so many versions of his journey.

However there is no doubt that “Doubting Thomas” played a crucial role in spreading Christianity to far corners of the world, far away from the religion’s birthplace.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I love this story of immigration and of faith. I wish all in charge of governments would look to new arrivals “as human beings, worthy of land, shelter, and the dignity of a future yet unwritten.”

LikeLiked by 5 people

We feel uncomfortable even sleeping on an unknown bed – I simply cannot imagine the pain and suffering felt by someone losing their home and homeland and journeying through uncertainty to an unknown destination.

I simply wish human beings were more human.

LikeLiked by 5 people

That and knowing that the change in location was not temporary. Never seeing one’s home town, or neighbors, or friends again…

LikeLiked by 3 people

Integration, immigration, love in despair, understanding instead of judgement, courage when faced with fear 😨, prayer 🙏 ♥️ when faced with darkness, praying for our politicians and leaders it is by no means an easy job

LikeLiked by 2 people

That is so true “it is by no means an easy job.” Prayer is very powerful indeed, especially effective for anyone who believes in it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a beautifully immersive and evocative piece. Your prose is rich with sensory detail and historical depth, drawing the reader seamlessly into a journey of exile, faith, and belonging. The way you weave history, legend, and human emotion gives the narrative both gravitas and grace, making it linger long after the final line. A powerful, compassionate telling that honors memory, resilience, and the quiet courage of arrival.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Dear Verma’ji, if my stories can linger in the minds of my readers, then there is no greater reward for writing them. I am elated to receive your heartfelt appreciation. I treasure every word of it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Dear friend, thank you for your generous and gracious words.

I’m truly glad my appreciation resonated with you. If your stories linger in readers’ minds, it’s because they are written with sincerity and heart—and that is a rare gift. Wishing you continued joy and inspiration in your writing journey.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much Verma’ji, your best wishes and encouragement mean a lot to me.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Ned for sharing my latest story in your blog. Now so many more people will come to know about this version of the history behind how and when Christianity first came to India.

LikeLike

Your stories are so rich in detailed descriptions. It is as if you bring us every sensory stimulus possible to make us feel we are there back so many years ago. You know so much history that you bring alive with sensory details. You are a master of language and rich detailed sensations so we see, hear and smell the tale you tell.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I try my best to evoke sensitivity through my stories. It is a very important part of any tale I tell. I am really thankful that my stories find such readers like you who recognise and feel these sensitive bits in my stories. Thank you so much for constantly appreciating.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this thoughtful post. I have been aware of some of this history for many decades. We lived in Syria for several years in the 1980s, and our first daughter was born there. Since then we have spent a lot of time travelling overland in India. I even bought this book for our daughter—The Kerala Kitchen: Recipes and Recollections from the Syrian Christians of South India.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That is so nice to hear. A story always becomes more special if you have been to some of the places mentioned in it, and experienced bits and pieces of the sights, sounds, and smell.

I love both Syrian and Keralite food. They are so amazing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

They are wonderful cuisines.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh, certainly they are exquisite.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wonderful Post and Story my Friend…God makes a way for His people, even through exile and fear.Faith carried by mercy, courage, and hope still bears fruit today.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That is so true, God always holds the faithful in his embrace. Though we may seem to be suffering, He is always there for those who believe in Him and also for those who do not believe.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Amen, so true. His love never lets go. Even in suffering, His presence remains.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amen to that brother.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙏

Aum Shanti

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much for liking the story.

LikeLiked by 2 people

As I was vaguely familiar, Trishikh, with the Christians in Kerala, I loved your wonderfully detailed story, as always, beautifully written by your talented hand. There is an old saying: “If only we could be more like humans should be, it would be a paradise on Earth.”

Every time I read one of your extraordinarily fascinating stories, I know for sure that one day you are going to be read and admired worldwide! Thank you, Trishikh, for today’s tale!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 3 people

Dear Joanna, as always your appreciation brings me great joy. May your words come true, and one day my stories be published, and find a wider audience.

Yes, if only we were a bit human, what not could we have achieved.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Trishikh, for the wonderful reply! As always, you are more than welcome!

Joanna

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a breathtakingly vivid and soul-stirring tale, Trishikh—your prose paints Thomas Cananeus’s epic journey with such poetic fire and historical grace, weaving faith, exile, and India’s timeless hospitality into a hymn that lingers long after the final word!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Dear Dinesh, so happy that you liked the story so much. Especially the imagery and historical inputs. Nothing gives me more joy than my stories lingering in the minds of my readers.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This narrative beautifully captures the moment Syriac Christians first touched Indian soil. It serves as a powerful testament to the inherent grace of Indian civilization—a land where the ancient ethos of ‘humanity first’ allowed a foreign faith to find a home. It’s a moving reminder that when we lead with openness, history becomes a story of harmony rather than conflict.

LikeLiked by 6 people

Dear Indrajit, I especially like it when you say “when we lead with openness, history becomes a story of harmony rather than conflict.”

Thank you for your beautiful comment

It has given me much joy and encouragement to keep on writing these stories.

LikeLiked by 3 people

We learn so much from each story of yours. Loved every bit of the story.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much Sumita, so glad that you liked this tale too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

thank you once again for adventure with education! 🙏🏼👍🏼😊🥰 ❤️

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is I who must thank you for your constant appreciation for my stories.

LikeLiked by 2 people

your stories are deserving of such appreciation! & it is my pleasure to provide it! 🌹🙏🏼❤️💃🏻🥳🥰🌹👍🏼

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this. Breezes filled with cardamom, cloves, jasmine, and mango blossoms? What lovely evenings that must create. Your ability to create atmosphere is as intoxicating as the scents themselves.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Wonderful story. Well done, and I wish you many blessings and a Happy New Year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Edward. So glad that you liked the story. A very Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to you and your family in advance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome, and thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

another classic here friend, historical in all its majesty, be proud..

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much William. Always a pleasure to be able to write and share such a story.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well said

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A people being welcomed as human beings – and a future sealed not by war but by shelter. How perfect would that be. A very thought provoking article – thank you.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That is so true, it (people being welcomed as human beings) seems impossible in the present day world, where even countries that allow refugees, many a times fail to provide human conditions for such refugees.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This narrative is a grand symphony between history and the soul. The way you paint the journey from Cana to the Coconut Coast transforms suffering into a long, poetic prayer. The warmth in the King’s welcome that you described feels like an embrace for anyone who has ever felt lost. Thank you for reminding us that home is not just a place, but a sincere acceptance.

LikeLiked by 6 people

Dear Livora, as always your thoughtful reflection on my story brings me immense joy. I especially like it when you say “home is not just a place, but a sincere acceptance.” This line of yours adds an underlying depth to my story. Thank you for your beautiful comment. I really treasure this.

LikeLiked by 2 people

An excellent prosaic composition, that is also relevant in relation the contemporary issues of mass migration. In the past many immigrants came to escape politically and prosecution from established religions, but there was also the attraction of the seemingly unlimited economic opportunities and the abundance of free land that could accommodate the forced displacement of prosecuted people. No such opportunities exist today; humanity is loosing its way.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much for your beautiful words. They never fail to give me much joy and encouragement to continue writing such stories.

Yes, it is indeed a pity that displaced people can’t find a place to call it their new home these days. The shortage of liveable land growing population poses a great problem, but if there is love and acceptance in the heart, refugees can always be treated better.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Beautiful story Trishikh. I wish that all refugees were greeted in such a loving and welcoming way.

Happy Holidays, whatever holiday you celebrate. Tomorrow is Solstice. May the light finally be fully restored.

love, katelon

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Katelon, it is so unfortunate that irrespective of so of human development, we humans have failed to look after fallen fellow humans. Yes, it is sad indeed. I can only be hopeful that this will gradually change, and we would become more concerned and more human as we evolve.

Happy Holidays to you too. We are in the Christmas mood right now.

Lots of love and blessings to you and your family too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A gripping and vivid portrayal—your writing brings history, courage, and the resilience of the human spirit to life. The hope and determination of Thomas and the refugees leap off the page. 🌅⚓📜

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you so much for your beautiful retrospection on my story. It gives me great joy to know that you find my writing vivid and gripping. As you already know, descriptions are a very important part of my story – I always want to transport my readers to the time and place of the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Trishikh – this is such heartwarming story of inclusion and acceptance; perfectly timed to commemorate universal love, something I have always perceived as the cornerstone of Christian faith.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That is so true – universal love is certainly the cornerstone of Christianity and many other religions. It is we humans who corrupt religion and sometimes give it a bad name.

I am so happy that you liked the story. Always a pleasure to receive your appreciation. Thank you so much.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The way you described the coast and the landing pulled me right in. And the idea of faith arriving through shelter and dignity not conquest felt especially relevant today. Strong piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Vidisha, it’s so nice to hear from you. I am really happy that the description of the Malabar coast and the landing appealed to you so much. I thought a lot while writing the description. So your words give me a great sense of accomplishment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As always, beautiful and magical storytelling, dear Trishikh. Your voice stands as a profound and compassionate presence for humanity in these challenging times. We wish you and your family a joyous holiday season and look forward to your future stories. All our very best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear friend, thank you so much for your beautiful words of encouragement. I really treasure them. So glad that you enjoyed this story of mine.

Seasons Greetings to you and your family too.

LikeLike

★˛˚˛*˛°.˛*.˛°˛.*★˚˛*˛°.˛*.˛°˛.*★*★* 。*˛.

˛°_██_*.。*./ \ .˛* .˛。.˛.*.★* *★ 。*

˛. (´• ̮•)*.。*/♫.♫\*˛.* ˛_Π_____.e ˛* ˛*

.°( . • . ) ˛°./• ‘♫ ‘ •\.˛*./______/~\*. ˛*.。˛* ˛.*。

*(…’•’.. ) *˛╬╬╬╬╬˛°.|田田 |門|╬╬╬╬╬*˚ .˛

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Cindy, a very Merry Christmas to you and your family too.

LikeLike

“This is a beautifully woven tale of courage, faith, and resilience. The journey of Thomas Cananeus and his people is so vividly told that you can almost feel the sea breeze, hear the market chatter, and sense the hope in every step on Kodungallur’s shores. A powerful reminder of how human perseverance and compassion can plant lasting legacies across generations.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Anjali, thank you so much for your beautiful words of appreciation. I really treasure them. Comments such as these give me much encouragement to continue writing these stories.

I am so happy that you felt like the sights, sounds, and smell of the time and places came to life in the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure Sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just the story to read during Christmas. India has always received everyone with a big heart. The story is so beautifully woven with vivid descriptions, that is seer pleasure to dive into it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, many of my stories during this December have been Christian centric. Am so glad that you liked this tale too. I strongly feel that descriptions can really take a simple story to a different level.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We simply love to celebrate every festival that comes in the calendar. ‘Baro mashe tero parbon’ as the saying goes. Your stories for December added to Christmas vibes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“That was the idea” glad the stories came out good. Keep an eye out for the next story on Friday as usual.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sure, I will. It’s a delight to read your stories. Almost like waiting for the next Annondomela. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mentor that got me into medical school is from a family of doctors from Kerala. In 1866, Welsh missionary Robert Jermain Thomas died at 27 on Korea’s Taedong River, flinging Bibles from a burning ship and offering one to his killer while shouting “Jesus!”

Koreans used those Bible pages as wallpaper in a home. Visitors read them. Curiosity sparked faith. Decades later, Pyongyang became the “Jerusalem of the East”—a massive revival exploded.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was the Lord’s will for me to suffer at med school He had greater plans for me 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

As Jesus said in John 12:24: “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amen to that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Lord’s plans are beyond our comprehension.

LikeLike

Your comment gives me much joy. I am so happy that you could relate to the story so well. Kerala has many christians.

Your story about Robert Jermain Thomas is so interesting. I did not know about him. Will read up on him.

I though know a bit about the revival in Korea. It is massive indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Again a story of human survival and faith. It’s sad that our society is becoming a centre of religious persecution, distrust and destruction. Diversity is becoming stronger and unity fumbling in darkness.

Having been educated in a convent school till middle classes Christian teachings have a deep impact on me since my formative years. And then Christian friends in the office…the bond seemed to be preordained.

LikeLiked by 3 people

You are very right, we seem to be moving away from unity. Differences in beliefs come in the way of basic humanity unfortunately. It has always been there in human history – this aggression towards someone else’s belief. Sadly we are living in a time, when it is quite active.

Christian or Convent education is still considered very prestigious in India, for all classes of society. I too had my schooling under the Irish Christian Brothers at St. Joseph’s College, in Kolkata, and College under the Jesuit Brothers at the St. Xavier’s College in Kolkata. Professionally I have worked with various Church based and other Christian Organisation, and also am a practicing Christian. So I have seen the religion up close.

Unfortunately the Church today like many or any other human institution comes with its share of miscreants, but then there are good people and good deeds too.

Thank you for your beautiful comment. I really like these interactions. They go so much beyond my stories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Congratulations on the new book!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Dawn. Always treasure your support and appreciation.

LikeLike

Welcome to visit my new blog page. Thank you http://www.etc4travel.wordpress.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Saif I do not usually allow comments or links unrelated to my stories, but I am allowing your travel link as through it perhaps people can visit India. And my stories are to enlighten people about India.

LikeLike